It is probably safe to say that there is much hubbub in everyone’s life. As we potter about, making sense of our lives – prioritizing ‘this and that’ for Monday mornings; strategizing in great detail about the unknown future; and secure that we have learnt from our past, even when less than one percent of all the facts are known to us – it has got me thinking on the conjoins of two phrases. “Greatness shall endure!” – and “This too shall pass!” If there is something whimsical in my approach this blog, then it is no doubt because I’m surrounded by the noise of many, especially in public life, who take themselves far too seriously.

Last year in Mumbai, in a moderated discussion between myself and Ustad Zakir Hussain – on the alignment of Western and Indian musical traditions – it was not surprising to me at all, that the conversation delivered philosophy and depth. Rather than a precisely boxed, ‘neatly wrapped and bowed’ chronology of ‘this and that’ and how we differ here, and are similar there, there was a realization that musicians – ‘those who deal in the art of producing sound’ – were after the same goals, in the same ways, with the same aspirations and with the same support of connective audiences. (The full talk appears on this website.)

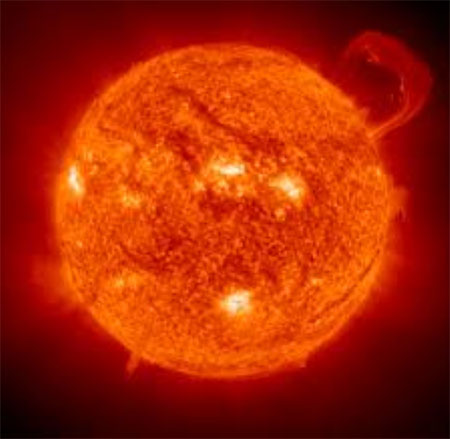

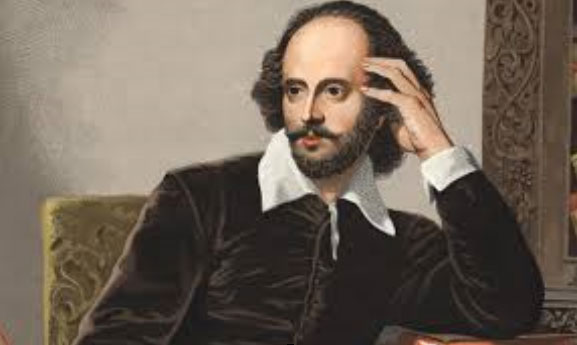

Every time we seek to succeed – it seems I am reminded that the only way to do so is to examine the big picture, and where we might exist in it. I did mention in that talk an absolutely mind boggling theorem, that was put forward by Sir Martin Rees, Lord Rees of Ludlow – Astronomer Royal. What a great title to hold. I first came to hear of it in the extraordinary output of the late Christopher Hitchens, and have unabashedly stolen it to make my point whenever appropriate. If, as Chris Hitchens stated, “we have in us the capacity for awe”, then it will be while imagining this theorem of the big picture and our place in it. Our great sun, Amon Ra, Shakespeare’s “hot eye of heaven”, Apollo’s chariot, the giver of life – also known as our relatively small and insignificant local star is about 4.5 billion years old – half way through its 8 billion year life cycle. It is not possible that sentient beings would be on the earth at the end, because long before that the Andromeda Galaxy, speeding on its current trajectory, will have collided with our own and ‘who knows?”. But let’s just play out the ‘what if?’ It should be an ‘arresting thought’ that if there were sentient beings in another 4 billion years that might have the opportunity to look upon the death of our star, they would be as different from us as we are from bacteria. The march of evolution, whether fleetingly understood or completely denied, does not care and does not stop. It puts into perspective the self-absorbed, self-important thought that suggests we, in our current form, are the last and perfect specimen. This is the grand reckoner of the phrase, “This too shall pass”. A phrase often used to remind us in the confusions of our humanity that no matter what holds importance in our conscience at any one time, it is likely to be less important as time goes on.

Does greatness endure even for our minutiae? We all mark the 400th death anniversary of William Shakespeare, this month. How long will this greatness endure? It is a solid tradition passed from generation to generation that insists that we examine the bard’s work. But I’m talking of a tradition that is only – by its largely Victorian revival – about two hundred years old. Will it last? I’m sure that Plato, Horace, Cicero, Ovid, Virgil, along with Chaucer and countless other philosophers and poets, once held the common man’s attention, as Shakespeare does today, but are now only remembered in specialist academia. As mentioned before, one hundred years ago this April we were embroiled in the Great War, the war that changed the face of society, never to be repeated and never to be forgotten – and who remembers that? Also as mentioned before, our new age millennials, of whom another 1 billion will be born by 2030, will not come to these ‘great and enduring’ themes, unless coerced to do so.

I’m also reminded of the enduring nature of our grand institutions. As recently as the accession of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953, few around the world, leave alone her British subjects would have contemplated a constitutional change that would render the monarchy obsolete. Who could imagine a one thousand year tradition pummeled into the dust of fleeting modern politics and expediency. As recently as the accession of Pope Pius XII to the Throne of St. Peter, in 1939, the monolithic church he ruled in absolute and infallible terms seemed bound to go on unchanged. And yet, a two thousand year tradition of political, spiritual and temporal power is splintering before our eyes. Our institutions are threatened – if not weakened – by the self-importance of individual human actions. In some cases, those institutions might do well for a little sunlight.

All things being equal, there is a democratic trend to bring everything into the sunlight – the great disinfectant of society. However, that means that there is a growing responsibility in the hands of the people to safeguard and watch over history, traditions that are worth keeping, and some sense of recording the ‘journey of man’ thus far. We have a serious problem. Our educational institutions have not kept pace with the population, creating a greatly touted democracy in the hands of the lowest common denominator. Can the people be trusted to keep, record, judge and hold what they do not know?

In the modern era there is no old. There is not even the time for something to be judged old. There is certainly no traditional reverence for anything old. Something from our lives 100 years ago, or even 50 years ago is not treated as part of our history, but weighed in comparison to our modern advancements and discarded completely. These out-of-date precepts or stylings are as insignificant as if they were one week old and judged unsatisfactory. It is our modern world. We don’t have a choice but to be in it, or be left behind by it. So where does that leave the two phrases – “Greatness shall endure” – and “This, too, shall pass”.

I have some wonderful musical scores on my table for review. Performances in London, and in Mumbai in the coming months will follow. Whether absorbing the popular Karelia Suite by Sibelius, the Hussain Tabla Concerto, Humperdinck’s opera Hansel and Gretel or Mahler 1 – I am struck by how personal our record of greatness might be and how different from one another. Like beauty, greatness might just be in the eye of the beholder, and if that is true, it must fade from generation to generation, unless it is revealed and passed on like a tradition. Mahler, in his inner workings announced that “tradition ist schlamperei” – “tradition is slovenliness”. Yes, in the creative world, this might be true. However, in the current environment, to a certain extent confusing creativity with repetition and capable of “losing the whole ball game” – tradition and its relevance explained to a modern generation might be all that remains before the lights go out.

It is with some irony and remorse that we might have to admit that ‘greatness’ is a judgement borne of the human condition – and therefore cannot endure. The phrase, “This, too, shall pass” is the only certainty, as time marches on. It’s not so bleak. Do your best in whatever lays before you – in the here and now. Enjoy strangers as if they were neighbors, friends and family – unless, of course, family and neighbors are dysfunctional, in which case don’t inflict that upon strangers. Uphold virtuous laws. Don’t take yourself too seriously. Be happy!

Many thanks!