After blogging on two topics as unrelenting as ‘climate change’ and ‘gun control’ – in as many months, I’m very gratified to return to music. Particularly because there is something in the offing that is sure to be of interest. Zakir Hussain’s new concerto for Tabla and Orchestra, entitled Peshkar is concert repertoire for the Symphony Orchestra of India not only for September, in Mumbai but on our forthcoming tour to Switzerland in January, 2016. As you might expect, thought processes in the last few months, during the writing of the piece and my ongoing dialogue with Maestro Hussain, have been rich and full. There is much to be said about the traditions of Western and Indian Classical music, their similarities and their differences, and I don’t suppose that this blog will begin to cover everything – but I write from a point of personal observation, which I hope readers will welcome. To provide some background and context for the thrust of this blog, here are some of my reflections on orchestral music. As a conductor, I can share unequivocally that there are many great things about conducting orchestras. They are ALL – without qualification – privileges and responsibilities.

After blogging on two topics as unrelenting as ‘climate change’ and ‘gun control’ – in as many months, I’m very gratified to return to music. Particularly because there is something in the offing that is sure to be of interest. Zakir Hussain’s new concerto for Tabla and Orchestra, entitled Peshkar is concert repertoire for the Symphony Orchestra of India not only for September, in Mumbai but on our forthcoming tour to Switzerland in January, 2016. As you might expect, thought processes in the last few months, during the writing of the piece and my ongoing dialogue with Maestro Hussain, have been rich and full. There is much to be said about the traditions of Western and Indian Classical music, their similarities and their differences, and I don’t suppose that this blog will begin to cover everything – but I write from a point of personal observation, which I hope readers will welcome. To provide some background and context for the thrust of this blog, here are some of my reflections on orchestral music. As a conductor, I can share unequivocally that there are many great things about conducting orchestras. They are ALL – without qualification – privileges and responsibilities.

There was a time that the conductor played a keyboard and was an included, seated member of the ensemble. The tradition of the modern conductor waving a baton is a relatively recent one, if one doesn’t count the “cheironomy” of the medieval monks. Audience members have reveled in attending concerts with their eyes – rather than their ears – and conductors have been transformed in those highly imaginative eyes into some wizard with a wand – on whose command the whole business revolves. No, the conductor is in the service of the music, and in the service of the musicians as they journey together in that music. Even the term ‘conductor’ implies ‘leading’, which to my mind is not exactly the right sentiment. The conductor must allow the music to be expressed, in the most natural way possible, (in the words of the great Herbert von Karajan – “do not disturb it”) with the full will of the players in front of him, but in such a way that they are convinced of the direction and course that he has set for them. The extraordinary realization of his idea – as if it were theirs. It is – in effect – the world’s greatest psychological connection and therefore the world’s greatest collaborative experience – bar none. As any orchestral musician will tell you, it is an enormous and joint privilege for everyone on the platform.

In the western tradition – we are in service of the music, no doubt. Music written by someone else, often times many years prior. Our performances are often seen in sacred terms, as if the score was the bible – and the concert performance the sacred intoning of the gospel during mass, where everyone is silent and reverent, and where a rulebook of tradition unfolds without question. We are, in effect, priests of music. For years we have all studied the code of deconstructing a score. We have pored over it and reviewed it and seen it from different angles, like theologians or – more often than not – like judges about to rule in a case. We have precedent. We have merits. We have a lot of due process. We may learn from our friends and our experiences, the way a court learns from ‘amicus curiae’ briefs. And we might occasionally find something new in ‘dormant’ language. We go about our task with a lofty pursuit of perfection. We present music to an audience in terms of Swarovski crystal. Art that they might not touch nor get too close to, but simply marvel at from afar as to the perfection of it all. Marvel at how well we have followed the rules, and how well we have presented the tradition. For the sake of my ‘intoning the gospel’ analogy – we would have presented a perfect Pontifical High Mass in the Extraordinary Form. The audience – congregation like in their demeanor – would have been uplifted in reverent silence.

In the western tradition – we are in service of the music, no doubt. Music written by someone else, often times many years prior. Our performances are often seen in sacred terms, as if the score was the bible – and the concert performance the sacred intoning of the gospel during mass, where everyone is silent and reverent, and where a rulebook of tradition unfolds without question. We are, in effect, priests of music. For years we have all studied the code of deconstructing a score. We have pored over it and reviewed it and seen it from different angles, like theologians or – more often than not – like judges about to rule in a case. We have precedent. We have merits. We have a lot of due process. We may learn from our friends and our experiences, the way a court learns from ‘amicus curiae’ briefs. And we might occasionally find something new in ‘dormant’ language. We go about our task with a lofty pursuit of perfection. We present music to an audience in terms of Swarovski crystal. Art that they might not touch nor get too close to, but simply marvel at from afar as to the perfection of it all. Marvel at how well we have followed the rules, and how well we have presented the tradition. For the sake of my ‘intoning the gospel’ analogy – we would have presented a perfect Pontifical High Mass in the Extraordinary Form. The audience – congregation like in their demeanor – would have been uplifted in reverent silence.

As I have often put forward, the rule of silence at classical concerts is better explained by a painting analogy. We concede that we are not original creators of the music as the composer was. We have no way of following all our personal impulses to change the format of that creation. We are recreating it anew in space and time, as if we were creating it spontaneously, but we are boxed in by the composer’s code book and our precedent and rules for following that code book. So imagine we had Leonardo Da Vinci’s masterpiece, The Mona Lisa off to one side of the stage. In the concert that followed we would be required to recreate, repaint The Mona Lisa, on a new surface, taking only two hours to do so, working in silence, unable to confer amongst ourselves, unable to make mistakes, or correct errors as we went, while an appreciative audience looked on, marveling at the techniques used to present the copy.

As I have often put forward, the rule of silence at classical concerts is better explained by a painting analogy. We concede that we are not original creators of the music as the composer was. We have no way of following all our personal impulses to change the format of that creation. We are recreating it anew in space and time, as if we were creating it spontaneously, but we are boxed in by the composer’s code book and our precedent and rules for following that code book. So imagine we had Leonardo Da Vinci’s masterpiece, The Mona Lisa off to one side of the stage. In the concert that followed we would be required to recreate, repaint The Mona Lisa, on a new surface, taking only two hours to do so, working in silence, unable to confer amongst ourselves, unable to make mistakes, or correct errors as we went, while an appreciative audience looked on, marveling at the techniques used to present the copy.

The conductor would have made his assessment and study of the work. He would no doubt emphasize the painting’s many notable features, bringing his knowledge and experience to the project. Wood rather than canvas – the sense of perspective in the background, or translucent skin, or folds in the clothing, or the enigmatic smile, or the natural plant dyes used for colours. The resulting performance would reveal his understanding of the painting as conveyed by fine brushes, mixing of colours, refined palette choices etc. Since musicians paint in time and sound, any noise from the audience that interfered with the performance would be tantamount to the audience member throwing up bright unwanted paint onto the work in progress. In other words, an un-muffled cough is equivalent in decibel value to a mezzo-forte horn. But please let’s put this in perspective.

I’m strongly convinced that silence in the audience should come genuinely as a result of appreciating the silence between movements. It should not be forced on audience members by self-appointed ‘manners police’, especially against fellow patrons who have presumably also paid to attend. Applause to a performer is like soul food. To enforce a ‘silence’ restriction without understanding it is to suggest that a savvy audience member should not clap after the scherzo of Schumann’s Second Symphony – an eminently applause worthy moment of orchestral virtuosity – and one in which an audience that remains silent has simply ‘missed the boat’ on what has just taken place. Also, this ‘rule’ of silence is relatively new, dating from the turn of the 20th Century and largely responsible for transferring western classical music into its current church environment. The silence would have been unknown, painful and damning to Mozart, Beethoven, and countless composers that followed. We should remind ourselves about longstanding ‘traditional’ audience behavior at the Opera or the histrionic music of Liszt’s piano repertoire which is directly connected to the hysterical behavior of his audiences, – crooning men and swooning ladies. All part and parcel of the rich experience.

Mozart would have expected the applause, sometimes during the music itself as opposed to between movements. It showed that the audience knew and appreciated what he was trying to present. If you read his letter to his father Leopold on the occasion of the première of the Paris Symphony in 1778– he is so gratified by the Parisian response of whispers, spontaneous applause and vocal validation that he treats himself to a large ice cream at the Palais Royal after the concert. Without the applause he would have felt betrayed – as if he had failed. So just a word of caution to the many who police our concerts for the errant clap. We might be on the wrong side of history and the wrong side of performed music if we protest too much. Every time we protest we deny Mozart a little of his ice cream – a heavy weight that we cannot reasonably be expected to bear. From my perch on the podium, I’m far from advocating for a noisy audience. It is one of the most distracting and unsatisfactory sensations but it is important to come to this issue with a holistic approach. Sometimes something comes along that puts all this strait-jacketing in perspective. I explained the sentiments above so that I can now break away from them.

Mozart would have expected the applause, sometimes during the music itself as opposed to between movements. It showed that the audience knew and appreciated what he was trying to present. If you read his letter to his father Leopold on the occasion of the première of the Paris Symphony in 1778– he is so gratified by the Parisian response of whispers, spontaneous applause and vocal validation that he treats himself to a large ice cream at the Palais Royal after the concert. Without the applause he would have felt betrayed – as if he had failed. So just a word of caution to the many who police our concerts for the errant clap. We might be on the wrong side of history and the wrong side of performed music if we protest too much. Every time we protest we deny Mozart a little of his ice cream – a heavy weight that we cannot reasonably be expected to bear. From my perch on the podium, I’m far from advocating for a noisy audience. It is one of the most distracting and unsatisfactory sensations but it is important to come to this issue with a holistic approach. Sometimes something comes along that puts all this strait-jacketing in perspective. I explained the sentiments above so that I can now break away from them.

If music is the thing we serve, there is no greater responsibility or honour that a conductor might have than to work with a composer on a new commission. I am in the enviable position of working with a world première of a new concerto written by Tabla Maestro Zakir Hussain. As far as I am able, I might write about my thoughts on the piece itself, and I certainly will provide a glimpse into its magic, but it is most unsatisfactory to write text about music that should be heard, felt and witnessed. It’s like writing a note about a poem, instead of presenting the poem itself. A waste of time. However, what has challenged and fascinated me is what elements of Western music we have lost to time and tradition and what great lessons can be reintroduced by examining the precepts of Indian classical music. I will be out of my depth in the latter, but my intuition about the ‘joins’ and the ‘bridges’ have been too strong to discount.

One is the visceral way in which Indian music is enjoyed. Like jazz, the listener is impelled to approve and encourage the performer in his personal journey through a different rule book. The rule book in this case is simply suggestive of a framework, and the audience revels in how well the personal journey of the performer might diverge, converge, drift, return or renew – within this framework. There is no arm’s length marveling at something too precious to disturb. In fact, the bond between performer and listener is a vocal, impulsive, noisy validation and without it the performer senses an empty betrayal. There is no perfection of dotted ‘i’s and crossed ‘t’s. There is only the perfection of the ‘rasa’.

‘Rasa’ – if I have understood it as a concept – is that special extra that all music should have. It can be as obvious as the connection between performer and audience, or it can be the bending of the phrase, the ‘turn of phrase’ as we say in Western parlance. It can be that delicious delay in the sounding of a note that brings the listener out of their seat. There is also a pervading spiritual sense to all Indian music that suggests that it is a privilege to be holding it in our hands, and that it must return to another realm, unharmed and enriched by having been with us. This instantly reminds me about the phenomenology of sound as spoken of by the late Maestro Sergiu Celibidache, Maestro Barenboim, and others as they have grappled with the ‘going out and the coming in’ of the sound – and more importantly the continuing tension of the sound that may be in the silence in between. This is very important to both east and west. However, it is perhaps more present in Indian music, and is sometimes less so in Western music, because the legal codes of each tradition allow or prevent the constant presence of it. Another factor that makes ‘rasa’ elusive in the western musical tradition is the group dynamic of large ensembles, which must emanate their collective spirit as ‘one force’ to achieve this great intangible characteristic, whereas the Indian performer, usually a single voice, can instinctively project it, without gathering others to him.

I’m happy to debate this point, but the unison plainsong of the monks was the last time we consistently and completely had some instinctive ‘ras’ in the west. Whether, Frankish chant of Charlemagne’s choir school at Aachen –or the chant of Santiago de Compostela in Spain– this was the last time that spiritual weaving of a unison nature was centrally apparent in western music. In the case of Spain, the distance between Santiago de Compostela and Rome resulted in a lack of centralization and the resulting Mozarabic chant is so florid, decorated and ornate that it is a perfect expression of the personal ‘ras’ of the local environment and mirrors the art and architecture to boot.

I’m happy to debate this point, but the unison plainsong of the monks was the last time we consistently and completely had some instinctive ‘ras’ in the west. Whether, Frankish chant of Charlemagne’s choir school at Aachen –or the chant of Santiago de Compostela in Spain– this was the last time that spiritual weaving of a unison nature was centrally apparent in western music. In the case of Spain, the distance between Santiago de Compostela and Rome resulted in a lack of centralization and the resulting Mozarabic chant is so florid, decorated and ornate that it is a perfect expression of the personal ‘ras’ of the local environment and mirrors the art and architecture to boot.

Then in Paris came the addition of a second and third line of harmony, in the great Notre Dame school traditions of Léonin and Pérotin. But even then, that harmony didn’t have to be noticed, too slow as a pedal note to be perceived in changing sound, as long as it had spiritual significance – often placed in threes to honour the Trinity. Then came four part harmony, and the joys of rich sumptuousness, which drive the listener to transcendent passions and to be sure creates its own type of collective ‘rasa’ – a marvelous and powerful hook to the heart. But with the advent of four and five part harmony– came codes and regulations that gave us rules on parallel fifths as much as they gave us Palestrina. It began the long ‘straitjacket’ that delivered western music into the confines of its crystal prison of perfection and the intoning of the Gospel at High Mass, – as opposed to the saxophone riff in the smoke filled bar at 3 am. Both speak to the soul with immense power. In simplified terms, the singular, horizontal nature of Eastern music allows for a heightened brand of individual expression. The multiple, vertical nature of Western music, specifically extensive harmony, must compel the performer to seek perfection of sound between all the parts, not just in his or her own. One an act of self-expression, the other an act of worship. This dichotomy has presented both great puzzle and great potential in PESHKAR.

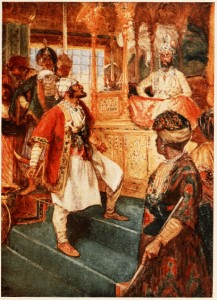

In this new concerto Maestro Hussain is careful to retain the structural integrity of ‘bandish’ as the ‘peshkar’ suggestively puts forward ideas that might be improvised upon later in the piece. The Peshkar was not only the historic figure that led a Moghul court through its daily schedule of events, – the man who introduced ambassadors, the man who managed people in and out of ‘the presence’ – but was the schedule itself suggesting a framework that had form, flexibility, order and command, all at the same time. The resulting work is a five movement piece which opens – as is the strong tradition – by giving the listener a misty and enticing glimpse of what may come, creating an intentional atmosphere of elusiveness. The piece moves on, providing pillars of structure as it goes. Using the tabla part as a bedrock the music weaves a thread incorporating solo lines for several instruments –prominent for the violin in a part originally intended for violin virtuoso Marat Bisengaliev. The composition is less about melody and more about atmosphere, which using pulse and colour is perhaps the only good way to construct a fine tabla concerto. The cadenza pushes through to the finale with its pulsing, rhythmic unison power for the full orchestra, creating a dazzling vehicle for both tabla and orchestra. This summary falls short – as words always do when describing music.

In this new concerto Maestro Hussain is careful to retain the structural integrity of ‘bandish’ as the ‘peshkar’ suggestively puts forward ideas that might be improvised upon later in the piece. The Peshkar was not only the historic figure that led a Moghul court through its daily schedule of events, – the man who introduced ambassadors, the man who managed people in and out of ‘the presence’ – but was the schedule itself suggesting a framework that had form, flexibility, order and command, all at the same time. The resulting work is a five movement piece which opens – as is the strong tradition – by giving the listener a misty and enticing glimpse of what may come, creating an intentional atmosphere of elusiveness. The piece moves on, providing pillars of structure as it goes. Using the tabla part as a bedrock the music weaves a thread incorporating solo lines for several instruments –prominent for the violin in a part originally intended for violin virtuoso Marat Bisengaliev. The composition is less about melody and more about atmosphere, which using pulse and colour is perhaps the only good way to construct a fine tabla concerto. The cadenza pushes through to the finale with its pulsing, rhythmic unison power for the full orchestra, creating a dazzling vehicle for both tabla and orchestra. This summary falls short – as words always do when describing music.

In the forthcoming discussions, rehearsals and performances – this fascinating bridge between Indian and Western music will be crossed and re-crossed in a way that I hope will leave both traditions alive and unscathed. Although the right hand drum is pitched, the tabla provides for this connection so well because it is not going to pit a melodic pitched Indian instrument on the backdrop of melodic pitched Western instruments. Despite many attempts to ‘fuse’ in this manner – the expectations of audiences in the performance of pitched instruments – in both Indian and Western rule books – is so non-aligned that each audience feels strongly cheated by exactly what appeals to the other. This is one of the main reasons that ‘fusion’, as we have come to understand it, is dissatisfactory. This is made more apparent if the ‘fusion’ serves as some gimmick as opposed to – first and foremost – serving the music. The process however, with PESHKAR is quite different. I will be ever conscious of the fact that there is something new to be learnt in both traditions – from each other – as they coexist and unfurl without a hint of damage to one another. The nature of the Tabla and its Maestro make this possible.

PESHKAR – commissioned by the National Centre Performing Arts, Mumbai – will be given its world première on September 25th , 2015 with a second performance on September 26th. The concerto will be performed with the Symphony Orchestra of India under my direction – at the Jamshed Bhabha Theatre, NCPA, Mumbai. The concerto will receive its European première, in January 2016 as the Symphony Orchestra of India embarks on a three city tour of Switzerland – the Zurich Tonhalle on the 19th, Geneva’s Victoria Hall on the 21st and St. Gallen Tonhalle on the 22nd. The repertoire will include Smetana’s Bartered Bride Overture and Bartok’s Concerto for Orchestra.

Zakir Hussain joins the orchestra and myself in his second concerto collaboration with the SOI – since the Triple Concerto for Tabla, Banjo(Bela Fleck) and Double Bass (Edgar Meyer) performed in 2013. This new world première provides an extraordinary opportunity for audiences to witness the viable joining of Indian and Western traditions and to continue their support for all of us on the platform. Just to make sure that we’re making the most of this experience –Maestro Hussain has consented to join me on stage in Mumbai on the evening of 24th September, to informally discuss precisely those ‘joins’ and ‘bridges’ that can widen our scope as musicians. The discussion will be moderated by Head of Indian Music Programming at the NCPA – Dr. Suvarnalata Rao – a consummate Indian musicologist who I’m sure will lead the conversation in her inimitable way into as yet ‘un-thought of’ territory. If you’re able- please join us at any of these events.

Many thanks!